Uncle Frank Atherton Recalls

Earlville IL Farmer Describes Life in the Old Days

by Alan Harris

|

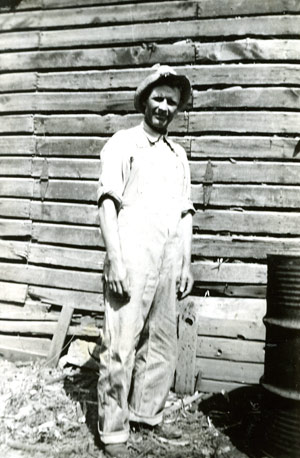

URING 1974 WHEN I WAS writing the Earlville IL news for the Ottawa (IL) Daily Times, I hit upon the idea of interviewing my great uncle, Frank Atherton, 83, for a feature article. The newspaper published the article at that time. Recently I discovered the article in my files and decided that it might be worth publishing in my Web site (May, 2012). In an interview Frank told me of his adventures as a farmer, bridge builder, ice harvester, and school board member, all in his "frank" manner. He was a man of definite opinions which were usually well-founded, and he was known by nearly everyone in Earlville (population 1,200) as a crusty, upright, good-hearted man. Every morning he would go early to the Post Office and sit on a bench provided there, talking with other old-timers about bygone days, and how things were going to pot in the present days. Asked what was the coldest winter he could remember, Frank responded quickly that it was 1936. "During January and February of that year the temperature never rose above zero for thirty straight days," he said. "On the coldest night of that spell, the temperature got down to minus 26 degrees." Frank told of a local mailman in that cold spell, who he said would verify this information if he were still alive. Andy Wold delivered the mail on foot to all his customers in the country since the roads were snowed in and there was no equipment in those days with which to clear them. Most of the other mailmen did not deliver their mail in this terrible weather, but Andy did. Frank recalled that the road which leads east out of Earlville formerly followed a different route. Instead of being an extension of Water Street south of the train tracks as it now is [1974], it was an extension of Brown Street north of the tracks. There was an old wooden bridge across Indian Creek just east of where Brown Street now turns north toward Rollo, and that old road went on east about half a mile to what was called the "high crossing," where it crossed the Burlington Northern tracks and then continued east. Eventually, he said, the old wooden bridge on that road became unsafe, and a new road was built in about 1933 south of the tracks, going across a new concrete bridge which Frank helped construct. Many a wheelbarrow-load of concrete was accidentally dumped into the creek (pronounced "crik" by Frank). "You had to steer the heavy wheelbarrow along a narrow plank. I was lucky and lost only one or two loads of concrete. Once it started to go, you had to let go of it or you'd be pulled in after it." Eventually, however, the new concrete bridge "went bad" and something had to be done about it. Luckily, this was about the time that plans were being made to build U.S. 34 through the area. The new highway was to run parallel to the tracks and immediately south of them. In preparation for the new highway, the bridges were all built beforehand, along with the installation of many culverts, which are still present in what are now fields. The U.S. 34 project called for a bridge north of the old concrete bridge (but still south of the tracks). The new bridge was built in the 1940's, according to plans. But then several Earlville residents took up the cause of having the new highway built on a different route, further south of what had been planned and was already begun. Many in Earlville objected to having the new highway run directly through the Earlville business district along Railroad Street. These residents eventually won their battle, and the previously planned route was abandoned following a court ruling. Thus, the new bridge across Indian Creek was left high and dry with no road attached to it. Since the older parallel bridge was weakening, some kind of transaction was made (Frank couldn't remember just what it was) by which the road's course was changed to take advantage of the new bridge. This bridge is still in use today [1974]. Frank recalled the record-setting trip of the Burlington's new "Denver Zephyr" in 1936. It ran non-stop from Denver to Chicago, averaging 77 1/2 miles per hour for the whole trip. He said that many people were gathered at the railroad crossings to watch it go through Earlville. Some days later, Frank recalled, he heard a small child say, "I saw the heifer when it went through town." Frank was born in 1891, and is now [1974] a good sturdy 83 years old with a keen sense of humor and a memory that is still crackling sharp. A widower, he lives alone in his large house on Ottawa Street, with a renter occupying an upstairs apartment. He does his own cooking and is celebrated for the pumpkin pies that he never fails to bake for church potlucks. He still helps his son Bernard with farm work during the busy seasons. He explained why there is such a roundabout set of curves on Route 34 west of Earlville, known as Moyer's curve. Many people wonder why the road couldn't have just gone straight through. "Well," Frank said, "it used to do just that. It went straight through and crossed over an iron bridge south of the present route. But since a new highway bridge had already been built further north, next to the tracks, the decision was made to use that bridge, so the highway was curved around to do this." As a result of this decision, many people have died on that curve in automobile accidents which might not have happened if the road had been straight. The country roads in Frank's time had no blacktopping and no gravel—just dirt or mud. Frank said that many times in the spring, just after a thaw, he would get a wagon, even an empty one, "balled up" in the mud. The mud would stick to the wheels and build up until the wheels would lock against the wagon box and refuse to turn any more. There was nothing to do then but get something to dig it out with.

Frank farmed for many years in Meriden Township, just northwest of Earlville. He used horses, of course, and was one of the last farmers in the area to buy a tractor. In the 1930's sometime, Frank related, a local tractor dealer came out to his farm one day, along with a factory representative from the tractor company, and told Frank, "Well, I came out to sell you a tractor." Frank said he turned around and told him, "Like the devil you're going to sell me a tractor. I know where your place of business is, and when I get good and ready, I'll come into town and buy a tractor, but you're not agonna sell me one now." With that the two men returned to Earlville. Later, in 1941, Frank finally decided to buy one, along with a corn picker, and from the same dealer, just as he had promised. The tractor is still in good running order, according to Frank, and is being used on his son Bernard's farm.

Before owning a tractor, Frank plowed with a two-bottom gang plow pulled by five horses. On a good day with good horses, he could get six acres plowed, starting about 6 a.m. and quitting about 5:30 p.m. He never worked Sundays or nights, and always got done with the farm work on time. He worked 320 acres for several years with one or two hired hands to help him. A hired hand was paid $35 to $40 a month, going up to $75 just before the Depression. A year afterwards he hired one of the same men back again for $25 a month. "One farm sold then for $65 an acre," Frank recalled. "The Depression made us all realize the value of a dollar. Some people didn't know where their next meal was coming from. It looks now like we might be heading for another depression—they say it won't happen, but I'm afraid it might, the way things are going." In addition to farming, Frank was a school director in his district for 30 years, serving many of those years as clerk, keeping all the records and paying all the bills. It was an elective position just as it is now in the unit district. He remembered one teacher who was hired for the country school. "She was no teacher. Every time any of the kids acted up she started bawling, and this is just what the kids wanted. They ran all over her. Finally, things got so bad that we had to call her in and talk with her. Her mother came along to the meeting. I gave her full authority to spank the kids and do whatever was necessary to keep order in the school. "I didn't think that would work, and it didn't. Finally, the teacher told us that we would have to expel all the kids from one family and a couple other kids (most of the school) or she would resign. We called a meeting and talked it over. I declared that we shouldn't expel anybody, but should stand firm. If she couldn't handle the kids, we would just have to accept her resignation. "Well, that's what happened. She resigned, and we hired another girl, just out of high school, on an emergency certificate, and she turned out to be the best teacher we ever had. I warned her she would have to make this bunch know she was boss. She did, and the kids respected her for it. Later one time I was talking to her about this, and she said she had been scared to death of those kids." A teacher in those days made $35 to $40 a month, Frank noted. A country school usually had from 12 to 15 students spread over eight grades. The teacher each day would teach one grade for part of the day, then another, and the children not being taught were kept busy with lessons or chores. Frank recalled that when he entered first grade, he had a teacher by the name of Robert Adams, who used to take Frank up on his lap. "He just did it to be friendly," Frank said, "and I was probably the only one in the first grade." Asked if he knew how ice was harvested for "ice boxes" (later replaced by refrigerators), Frank replied that he once helped with this. "There were two dams along Indian Creek, one north of town in Davison's woods, and one just south of what is now old U.S. 34. You had to have a dam in order to get the water deep enough and quiet enough to get good ice. "The way they harvested ice was to start upstream from the dam and cut a big hole about 12 feet square, then cut a narrow 2-foot channel leading downstream from the middle of the big hole. This channel was used for floating ice down to the icehouse for warm weather storage, and you used a 'pike pole' to help keep it moving. First the ice was marked off in squares with some kind of marker. "Then the men would use ice saws to cut out the blocks. These were floated down the channel and then put on chutes made of wood, which would carry them up to the door at the top of the icehouse. A team of horses would provide the lifting power to get the ice up there, and a rope with a 'dog' on the end of it would slide the blocks up the chute." Once inside the icehouse, the ice was stacked and packed with sawdust for insulation. Ice would keep in this way all summer, through the hottest weather. The ice was sold mainly for use in domestic ice boxes and meat-packing plants, since there was no mechanical means of refrigeration back then. Frank recalled that "husking bees" used to be a great attraction, bringing in hundreds of people. A Harding man, Theodore Tuftie, won the county contest in 1936, held on the Alfred Lee farm. He set a world record by husking 44.4 bushels of corn in 80 minutes. In the state contest in 1934, held at the Wilbur Stockley farm, Frank said he drove a team for a man named Stringfield or Springfield. "They wanted all gray teams, just for appearances, so I said I would drive mine. Old Will Stockley won the state contest. He was Wilbur's father." Asked how the contest was conducted, Frank replied, "The way they would do it was to have everybody start down a land when the gun was shot, husking corn by hand and throwing it into a wagon that went alongside. When the time was up an hour and twenty minutes later, the gun would go off again. Everyone stopped, and three or four judges would weigh the corn and examine it for too many husks still on the ears. Each man's total bushels was figured, and the one with the most bushels won. As a sidelight they also judged the best team of horses at the contest." Frank's wife Clara passed away in 1969. Their children were Bernard, Marjorie, and Charlotte. Frank himself passed away in early 1981 at the age of 89. |